Planted outside Village Cigars in New York’s Greenwich Village, a triangle covered in mosaic tiles sits on the sidewalk. An inscription reads: “Property of the Hess Estate, which has never been dedicated for public purposes.”

The triangle, cracked and barely noticeable at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Christopher Street, measures two feet on each side.

Once the city’s smallest privately owned piece of property, it tells a tale that goes back to the beginning of the 20th Century.

“It is emblematic of Greenwich Village,” says Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. “It’s the little guy fighting city hall.”

Greenwich Village was long the center of New York’s and the nation’s counterculture, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, but its history goes back to the early 18th Century.

Photo by: Gerard Albert III

The story of the Hess Triangle starts in 1910, when nearly 300 buildings in the West Village were condemned and slated to be torn down to build the Seventh Avenue subway line.

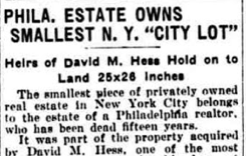

The New York Times reported in 1913 that buildings on an 11-block stretch were to be “ruthlessly cut through, destroying many curious residences and businesses.”

One of the casualties of the project was the Voorhis, an apartment building owned by the estate of David Hess. The Hess family refused to sell the five-story apartment building but, citing laws that permit governments to seize privately held land for public purposes, the city took it away.

By 1914 the only property remaining in the Hess family’s name was a triangle of land on the sidewalk, where the mosaic now sits.

How did this happen?

Land surveyors missed a portion of the land taken from the Hesses leaving them with about 0.0000797113 of an acre. The city asked the family to donate the sliver of land but, still upset by the demolition of the Voorhis, the Hesses refused.

The city is full of unusual plots of land left over after the construction project, according to Berman, but none as small as the Hess Triangle.

Greenwich Locksmith, at 125 square feet, is the smallest freestanding building in Manhattan. The 98-year-old structure is only big enough for one or two customers to fit inside, but the shop has served the Village for over 30 years.

For Berman, places like this represent the charm of old New York, before pricey restaurants and apartment buildings took over the Village.

A cigar store was built on the property adjacent to the triangle and, in 1922, the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger reported that Frank Hess, the estate’s executor, was summoned to New York to pay taxes on the parcel of land.

Photo by: Gerard Albert III

When he saw the property, “scarcely large enough for the erection of a slot machine,” he worked out a deal with the owners of the cigar store. They would set a marker on the triangle in the hope it would discourage the city from claiming it.

That’s how the mosaic plaque came to be. The last words of the inscription, “never been dedicated for public purposes,” echoes the spirit of the Hesses, who resisted the city’s attempts to take their property.

The owners of the store leased the triangle until eventually buying it for $1,000 in 1938. The cigar store now also sells electronic cigarettes and CBD gummies and is owned by Nehad Ahmed, who has been in the spot for 30 years.

“There’s a very cool story about that triangle,” he says, from behind the counter.

Gerard Albert III is a reporter in the Caplin News’s New York City Bureau.